Nombre de resultats 3

per a acme

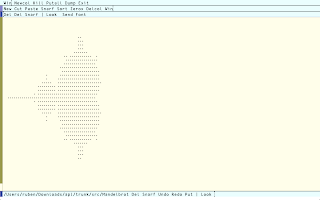

02/01/2014 - The Mandelbrot set in one line of APL

Is this line noise?

NOTE: if you are not seeing several Greek looking letters and arrows in the line above, some UTF8 stuff got wrong. Sorry, I'll try to fix it, drop me a tweet!

Nope. This is not line noise, but a complete APL program to display the Mandelbrot set in glorious ASCII, with asterisks and spaces just like Brooks and Matelski did a long time ago while studying Kleinian groups (it's a short paper, read it someday). I'll explain in (a lot, I hope) detail this line in a few moments. So, what's APL first?

APL is literally A Programming Language. Funny, isn't it? Its origins can be traced back to a way to formalise algorithms created by Kenneth Iverson while at Harvard. It is famed as a very cryptic language, for a reason. Its fundamental functions are unicode chars, and at first it feels extremely weird.

I got interested in it after finding an iOS interpreter for J, a programming language developed as a successor to APL, also by K.I. It just got away without Unicode, leaving only cryptic dygraphs, like <.@o. (from a Wikipedia example of high precision computing.) J is very cool, in that it offers a terse syntax to operate with matrices and vectors, very much like Matlab (Octave in my case) or R. But I felt I'd rather check the first idea, before diving into the even weirder syntax of J. So, it was APL.

The first problem was finding a good APL interpreter. Most were paid (and extremely expensive) and I could only find 2 APL interpreters working in Mac OS. One is NGN APL an implementation focused on node.js Also usable on a browser, so it is cool. But I'd rather get a little closer to the system... And decided to use Gnu APL instead. Of course, using an emacs mode for gnu-apl. Caveat: make sure to add

to your .zshrc or similar, without it you'll need to add a hook to gnu-apl mode reading

to make sure emacs and apl talk in utf-8. Without it, there are no commands to send to the interpreter!

Since I'm also a heavy acme user, and acme is well-known in its unicode support, I used it instead to develop that line above. But emacs works correctly, I just like having things to tinker with acme.

Getting back to the line-noisiness of APL, first you need to know that precedence is right-to-left, so

3×3+1

in APL yields 12 instead of the expected 10. You can change this with parentheses. Now that I have taken this out, we can analyse the line above. Instead of explaining it from right to left, I'll explain how I proceeded to develop it.

Put it succintly (I could explain a lot of the mathematics behind, but I just want to do a picture today) to draw the Mandelbrot set we need to find complex points c=x+iy (remember: you can think of a complex point as a point in a plane, like a screen: it has an x coordinate and a y coordinate) such that computing

f(z)=z^2+c

a lot of times with z=c is eventually a point outside a circle of radius 2. For instance, if c=1 this would be:

So the first part I wanted to get out of my way was generating this iteration. There are several ways to do it in APL, but a very cool way I found was to first generate the required computation like above. How?

computes exactly this, if m=c or if m is any other iterate, like m=f(f(f(c))). In APL speak, making m hold the same as c would be

and since right-to-left priority,

means "assign to m the value of c, multiply m by m (remember: it's the same as c) and add c." Likewise,

ends is computing the 2nd term in the list above, if c 1. So we have a pretty clear idea of how it should look like:

This is essentially "many times" the string " c+m×m" There's a very very easy way to repeat stuff in APL. For instance, 3 � 1 (read 3 reshape 1) creates a vector with three ones, 1 1 1. Reshape essentially multiplies or trims vectors. But... 3 � 'tomato' is 'tom'. The reshaping also cuts, of course! What we need is to make APL treat the string ' c+m×m' as one element. This is done with the next instruction in the Mandelbrot line, as you may guess: encapsulate.

ensures APL treats it as one element, so

generates a neat and long string of what the iterates should look like. To make sure the final string makes APL-sense, first we "enlist" with ∊. Turn the vector of repeated iterates into just one iterated element, like a long string all together. This could actually be removed, but it allowed me to learn a new function and I think it's pretty interesting. To end in a proper way, we add to the string a receiver variable 'z' and fuse the strings with comma.

I know this was long, but the iteration was the trickiest part!

Since APL is cool with matrices (and complex numbers!) we can assign to the initial c a whole matrix of complex points (our screen pixels) and then we'll have all the stuff required for the picture.

This weird piece is just a compact way of generating a grid. To make it easier to understand, �5 (that's iota 10) generates the sequence 1 2 3 4 5. To create a matrix we need two sequences (one for the x coordinates and another for the y coordinates.) For the complex numbers we can do 0J1 �× 5 which yields 0J1 0J2 0J3 0J4 0J5. As you may guess, 0J1 is just the complex number i. For some weird reason APL uses the j letter instead of i. No big issue. Now we have the x's which go from 1 to 5 and the y's which go from i to 5i Now we need to find all the complex points in the plane. This means adding one of each x to each y, to get a grid. Similar to a multiplication table, but with sums instead of products. APL magic to the rescue!

yields

which is pretty close to what we need. To plot the Mandelbrot set we are only interested (mostly, and in this particular instance) in points with real coordinate x between -2.1 and 0.5 and complex coordinate between -1.3 and 1.3 (just to make it square which is easier.) This long blurb just adds a matrix similar to the one above to a complex point, generating the grid of points we want, and assigns it to c. Almost done!

After we have the set of points in c, we merge this string (with comma) to the iteration we developed above. At the far right of the iteration we find this piece

As you may guess, this adds to the string 1+0<|z which from right to left does:

NOTE: The first version of this code had 0<|z, which works well for rough images of the Mandelbrot set, since most iterates are eventually INFNAN, which is a funny number in programming, since it is positive, smaller than 0, different from itself... Almost anything :D

We have a neat string which can generate a matrix of 1s and 2s and represent the Mandelbrot set. How do we make this string compute something? Magic!

� (known as execute) takes a string and computes it as an APL function. Magic! (just like eval in Lisp or Javascript, actually)

Since a matrix can be used to index a vector, we use this newly computed matrix as indexes (i.e. between square bracket) with the vector ' *' so we get almost a Mandelbrot set. But since I was slightly lazy when generating the grid of points, it is transposed. � (transpose) fixes it and finishes the program.

�' *'[�'1+0<|z',(∊150�⊂'�c+m×m'),'�c�(¯2.1J¯1.3+(((2.6÷b-1)×(¯1+�b))∘.+(0J1×(2.6÷b-1)×(¯1+�b�51))))']NOTE: if you are not seeing several Greek looking letters and arrows in the line above, some UTF8 stuff got wrong. Sorry, I'll try to fix it, drop me a tweet!

Nope. This is not line noise, but a complete APL program to display the Mandelbrot set in glorious ASCII, with asterisks and spaces just like Brooks and Matelski did a long time ago while studying Kleinian groups (it's a short paper, read it someday). I'll explain in (a lot, I hope) detail this line in a few moments. So, what's APL first?

APL is literally A Programming Language. Funny, isn't it? Its origins can be traced back to a way to formalise algorithms created by Kenneth Iverson while at Harvard. It is famed as a very cryptic language, for a reason. Its fundamental functions are unicode chars, and at first it feels extremely weird.

I got interested in it after finding an iOS interpreter for J, a programming language developed as a successor to APL, also by K.I. It just got away without Unicode, leaving only cryptic dygraphs, like <.@o. (from a Wikipedia example of high precision computing.) J is very cool, in that it offers a terse syntax to operate with matrices and vectors, very much like Matlab (Octave in my case) or R. But I felt I'd rather check the first idea, before diving into the even weirder syntax of J. So, it was APL.

The first problem was finding a good APL interpreter. Most were paid (and extremely expensive) and I could only find 2 APL interpreters working in Mac OS. One is NGN APL an implementation focused on node.js Also usable on a browser, so it is cool. But I'd rather get a little closer to the system... And decided to use Gnu APL instead. Of course, using an emacs mode for gnu-apl. Caveat: make sure to add

export LC_ALL=es_ES.UTF-8

export LANG=es_ES.UTF-8to your .zshrc or similar, without it you'll need to add a hook to gnu-apl mode reading

(set-buffer-process-coding-system 'utf-8 'utf-8)to make sure emacs and apl talk in utf-8. Without it, there are no commands to send to the interpreter!

Since I'm also a heavy acme user, and acme is well-known in its unicode support, I used it instead to develop that line above. But emacs works correctly, I just like having things to tinker with acme.

Getting back to the line-noisiness of APL, first you need to know that precedence is right-to-left, so

3×3+1

in APL yields 12 instead of the expected 10. You can change this with parentheses. Now that I have taken this out, we can analyse the line above. Instead of explaining it from right to left, I'll explain how I proceeded to develop it.

Iterating the quadratic polynomial

(∊150�⊂'�c+m×m')Put it succintly (I could explain a lot of the mathematics behind, but I just want to do a picture today) to draw the Mandelbrot set we need to find complex points c=x+iy (remember: you can think of a complex point as a point in a plane, like a screen: it has an x coordinate and a y coordinate) such that computing

f(z)=z^2+c

a lot of times with z=c is eventually a point outside a circle of radius 2. For instance, if c=1 this would be:

- f(1)=1^2+1=2

- f(f(1))=f(2)=2^2+1=5

- f(f(f(1)))=f(5)=25+1=26

So the first part I wanted to get out of my way was generating this iteration. There are several ways to do it in APL, but a very cool way I found was to first generate the required computation like above. How?

'c+m×m'computes exactly this, if m=c or if m is any other iterate, like m=f(f(f(c))). In APL speak, making m hold the same as c would be

m�cand since right-to-left priority,

c+m×m�cmeans "assign to m the value of c, multiply m by m (remember: it's the same as c) and add c." Likewise,

c+m×m�c+m×m�cends is computing the 2nd term in the list above, if c 1. So we have a pretty clear idea of how it should look like:

something�c+m×m�c+m×m�c+m×m�c+m×m�c+m×m�c+m×m�c+m×m�cThis is essentially "many times" the string " c+m×m" There's a very very easy way to repeat stuff in APL. For instance, 3 � 1 (read 3 reshape 1) creates a vector with three ones, 1 1 1. Reshape essentially multiplies or trims vectors. But... 3 � 'tomato' is 'tom'. The reshaping also cuts, of course! What we need is to make APL treat the string ' c+m×m' as one element. This is done with the next instruction in the Mandelbrot line, as you may guess: encapsulate.

⊂'�c+m×m'ensures APL treats it as one element, so

20�⊂'�c+m×m'generates a neat and long string of what the iterates should look like. To make sure the final string makes APL-sense, first we "enlist" with ∊. Turn the vector of repeated iterates into just one iterated element, like a long string all together. This could actually be removed, but it allowed me to learn a new function and I think it's pretty interesting. To end in a proper way, we add to the string a receiver variable 'z' and fuse the strings with comma.

I know this was long, but the iteration was the trickiest part!

Generating the grid of points

'�c�(¯2.1J¯1.3+(((2.6÷b-1)×(¯1+�b))∘.+(0J1×(2.6÷b-1)×(¯1+�b�51))))'Since APL is cool with matrices (and complex numbers!) we can assign to the initial c a whole matrix of complex points (our screen pixels) and then we'll have all the stuff required for the picture.

This weird piece is just a compact way of generating a grid. To make it easier to understand, �5 (that's iota 10) generates the sequence 1 2 3 4 5. To create a matrix we need two sequences (one for the x coordinates and another for the y coordinates.) For the complex numbers we can do 0J1 �× 5 which yields 0J1 0J2 0J3 0J4 0J5. As you may guess, 0J1 is just the complex number i. For some weird reason APL uses the j letter instead of i. No big issue. Now we have the x's which go from 1 to 5 and the y's which go from i to 5i Now we need to find all the complex points in the plane. This means adding one of each x to each y, to get a grid. Similar to a multiplication table, but with sums instead of products. APL magic to the rescue!

(�5) .+ (0J1×(�5))yields

1J1 1J2 1J3 1J4 1J5

2J1 2J2 2J3 2J4 2J5

3J1 3J2 3J3 3J4 3J5

4J1 4J2 4J3 4J4 4J5

5J1 5J2 5J3 5J4 5J5which is pretty close to what we need. To plot the Mandelbrot set we are only interested (mostly, and in this particular instance) in points with real coordinate x between -2.1 and 0.5 and complex coordinate between -1.3 and 1.3 (just to make it square which is easier.) This long blurb just adds a matrix similar to the one above to a complex point, generating the grid of points we want, and assigns it to c. Almost done!

Computing and plotting

�' *'[�'1+0<|z',After we have the set of points in c, we merge this string (with comma) to the iteration we developed above. At the far right of the iteration we find this piece

'1+0<|z',As you may guess, this adds to the string 1+0<|z which from right to left does:

- Compute the norm (distance to the origin) of the final iterate, which was assigned to z at the end of the iteration with |

- Check if this is larger than 4. This generates a matrix of 1s and 0s

- Add 1 to all entries of this matrix (so we have a matrix full of 1s and 2s

NOTE: The first version of this code had 0<|z, which works well for rough images of the Mandelbrot set, since most iterates are eventually INFNAN, which is a funny number in programming, since it is positive, smaller than 0, different from itself... Almost anything :D

We have a neat string which can generate a matrix of 1s and 2s and represent the Mandelbrot set. How do we make this string compute something? Magic!

� (known as execute) takes a string and computes it as an APL function. Magic! (just like eval in Lisp or Javascript, actually)

Represent it neatly

�' *'[stuff]Conclusion

Writing this line of code took me quite a long time, mostly because I was getting used to APL and I didn't know my way around the language. Now that I'm done I'm quite impressed, and I'm looking forward to doing some more fun stuff with it. And if possible, some useful stuff.22/05/2013 - Find Search Engine Rankings... via the Command Line

|

| Via pixelfrenzy@flickr |

Beware! The software described here is just for personal and very light use. Its use beyond purely recreational value is against Google Search terms of service, and I don't want you or anyone to step that line. Any use of this code is at your own risk.

Well, after this scary paragraph, lets get to the real meat. Which boils down to just a few lines of bash.

I'm a command line interface geek. I enjoy tools like taskwarrior or imagemagick. And every time I have to chew some data, I go down the command line route. In the last months I have found the incredibly effectiveness of awk, sed, head, tail and tr to convert what some web service spits into useful data I can feed to R to do something useful.

Today I was thinking about search rankings, and wondering if I could write a small tool that eased my occasional curiosity. Yes, I have done this by hand: search for some keyword and look through 8 pages of results looking for one of my websites. I don't do it very often, but sometimes it has to be done. And since I love automating things and the command line, I wrote the following blurb. I don't claim it is beautiful, but it works:

#/bin/sh

# Perform a web search in Google via the command line. Usage:

# automatic.sh "search term" domain pages

# domain stands for what goes after the dot in "google." and

# defaults to com. Pages is the number of search pages to

# process. Defaults to 1, since this script fetches

# 100 results per page.

domain=${2-com}

pages=${3-4}

span=$(seq 0 1 $pages)

for num in $span

do

iter=$((num*100))

# This sets the user agent to Lynx, a command-line web browser to

# let google know it's better if there is no javascript and fluff

# laying around.

wget --header="User-Agent: Lynx/2.6 libwww-FM/2.14" "http://www.google.$domain/search?q=$1&start=$iter&num=100" -O search$num -q

# Comments about this piping:

# The sed 'E'xtended command looks for patterns like

# href="/url=something", with the goal of grabbing that something:

# that's the result URL from the search. It captures this group

# and rewrites it as "SearchData, something" with several new lines

# for readability (in case you remove the grep pipe.)

# The grep is just used to prune all lines that are not search

# results, and then awk is used to print the search result number

# and the URL

sed -E "s/<[^h]*href=\"\/url[^=]*=([^&]*)&[^\"]*\">/\n SearchData, \1 \n\n/g" search$num | grep "SearchData" | awk "{print $iter+NR \" \" \$2}"

done

# The script leaves a lot of files named "search??" laying in the directory it

# is executed. In some sense this is a feature, not a bug. You can

# then do something with them. If you don't want them laying around,

# add rm search$num before done.

./automatic.sh "learn to remember everything" | grep "mostlymaths"

For extra fancy points you can use this to create reports inside Acme, if you are so oriented.

21/04/2013 - Just as Mario: Using the Plan9 plumber utility

Note: It's best to open the videos in full screen. Also I have added a few line breaks or readability in the code snippets that will make them not work correctly. It's not hard to find where they are, if you run into any problems let me know.

If you've been following this blog, you'll know I've been using Acme and related Plan 9 from User Space utilities lately. One of its pieces is the plumber. And knowing what it does may be tricky:

The Plan9 plumber is like open on steroids. Why?

Rules work in a trigger-and-fire way. A set of tests make the trigger, if the text you pass to the plumber matches, the rule is fired. In this case:

[1] This is needed. From the plumb manual section 7 (man 7 plumb or right click plumb(7) inside acme):

But we may get as fancy as we like, for example:

For me, its main strength is inside acme, since it is almost the only piece of Plan9 I use with regularity (I use zsh which is pretty good as it is.) As such, using the plumber we can add even more awesomeness to this editor:

This lets me write ag:word or ag:"something longer" to search for word or "something longer" recursively in the current working directory using The Silver Searcher.

The Silver Searcher is a source code file searcher, similar to ack. Ack and tss are both faster than grep because they omit .ignore, backup and non-source files. Of course this can be overriden, but since I usually work only with source when using grep, it is a great tradeoff.

The --search-files is a hidden option, without it line numbers are not rendered when ag is ran from another program (see this github issue).

Or I can add the following to use my wikipedia quick searcher script (based on this neat commandlinefu hack):

So I can write and use def:europium in case of need. Of course, it is far more handy to use acme's 1-2 chords for this: select europium with button 1, select wikiCLI.sh (the name of my script) with button 2 and without releasing, tap button 1...

As you can guess, this won't work in a 1-button Mac laptop without external mouse, since you can't press button 1 while pressing button 2... After all, button 2 is button 1 while pressing Alt. To make it work, I patched devdraw in plan9ports:

And now you can press Ctrl while having Alt pressed to send a "button 1" chord. Simple and innocuous patch.

If you've been following this blog, you'll know I've been using Acme and related Plan 9 from User Space utilities lately. One of its pieces is the plumber. And knowing what it does may be tricky:

Plumbing is a new mechanism for inter-process communication in Plan 9, specifically the passing of messages between interactive programs as part of the user interface. Although plumbing shares some properties with familiar notions such as cut and paste, it offers a more general data exchange mechanism without imposing a particular user interface.

What is the plumber?

It's somewhat hard to explain at first. I'll try to give you a simple example from Mac OS. In Mac OS you can find a command line utility named "open" (/usr/bin/open). From its manual entry you can read:open -- open files and directoriesSimple and easy. And it just does what you'd expect:

- open something.jpeg will open this image in Preview (or its default opener)

- open afile.txt will open this text file with its default opener, too.

- open http://web.something will open the webpage in the default browser.

The Plan9 plumber is like open on steroids. Why?

Plumbing superpowers

The strength of the plumber is two sided:- Completely configurable

- System wide (kind of)

Completely configurable

The plumber works with rules, and you can just write your own cool roles in a file ~/lib/plumbing What does a rule look like? Here is a rule to open an image using the Mac OS open utility:type is text

data matches '[a−zA−Z0−9_–./]+'

data matches '([a-zA-Z¡-￿0-9_\-./]+)

\.(jpe?g|JPE?G|gif|GIF|tiff?|TIFF?|ppm|bit|png|PNG)'

arg isfile $0

plumb start open $file

Rules work in a trigger-and-fire way. A set of tests make the trigger, if the text you pass to the plumber matches, the rule is fired. In this case:

- The type of the data has to be text (in fact is the only type the plumber handles)

- The content of the message has to match this regular expression [1]

- The content of the message has to match this regular expression, with groupings

- The argument group $0 (the whole regexp match) has to be a file, then the variable $file holds its full path

- THEN we run "open $file"

[1] This is needed. From the plumb manual section 7 (man 7 plumb or right click plumb(7) inside acme):

The first expression extracts the largest subset of the data around the click that contains file name characters; the second sees if it ends with, for example, .jpeg. If only the second pattern were present, a piece of text horse.gift could be misinterpreted as an image file named horse.gif.This relatively simple example is big enough to allow us to make pretty cool things with the plumber. Although this example only allows us to type plumb filename.jpg and the image will be opened via "open".

But we may get as fancy as we like, for example:

# isbn10 search through Amazon

type is text

data matches '([0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9]

[0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9])'

plumb start open 'http://www.amazon.com/s/?field-keywords='$1

- Type has to be text, as always

- Match exactly 10 digits (Plan9 regexes don't have brace count)

- Then search the ISBN through Amazon

System wideness of the plumber

When I say the plumber works system wide, I mean that in the Plan9 ecosystem (or in plan9ports) anything the plumber recognises as "special" can be easily plumbed. For example, I'm typing this in acme, thus I can right-click this ISBN (0836213122) to switch to Chrome and find what this book is. And if I'm in a 9term window, I can middle click-and-release to get the same. It's neat, but of course it gets neater: right clicking in an expression filename:lineno gets you to this match, making grep a whole lot more useful.For me, its main strength is inside acme, since it is almost the only piece of Plan9 I use with regularity (I use zsh which is pretty good as it is.) As such, using the plumber we can add even more awesomeness to this editor:

type is text

data matches 'ag:"?([a-zA-Z¡-￿0-9_\-./]+)"?'

arg isdir .

plumb start zsh -c 'ag --nogroup --nocolor --search-files "'$1'" '$dir'

| plumb -i -d edit -a ''action=showdata filename='$dir'/ag/'$1' '''

This lets me write ag:word or ag:"something longer" to search for word or "something longer" recursively in the current working directory using The Silver Searcher.

The Silver Searcher is a source code file searcher, similar to ack. Ack and tss are both faster than grep because they omit .ignore, backup and non-source files. Of course this can be overriden, but since I usually work only with source when using grep, it is a great tradeoff.

The --search-files is a hidden option, without it line numbers are not rendered when ag is ran from another program (see this github issue).

Or I can add the following to use my wikipedia quick searcher script (based on this neat commandlinefu hack):

type is text

data matches 'def:"?([a-zA-Z¡-￿0-9_\-./]+)"?'

plumb start zsh -c 'wikiCLI.sh '$1'

| plumb -i -d edit -a ''action=showdata filename='$dir'/wikipedia/'$1' '''

So I can write and use def:europium in case of need. Of course, it is far more handy to use acme's 1-2 chords for this: select europium with button 1, select wikiCLI.sh (the name of my script) with button 2 and without releasing, tap button 1...

As you can guess, this won't work in a 1-button Mac laptop without external mouse, since you can't press button 1 while pressing button 2... After all, button 2 is button 1 while pressing Alt. To make it work, I patched devdraw in plan9ports:

diff -r 1bd8b25173d5 src/cmd/devdraw/cocoa-screen.m

--- a/src/cmd/devdraw/cocoa-screen.m Tue Mar 19 14:36:50 2013 -0400

+++ b/src/cmd/devdraw/cocoa-screen.m Sat Apr 06 20:02:44 2013 +0200

@@ -847,7 +847,9 @@

case NSFlagsChanged:

if(in.mbuttons || in.kbuttons){

in.kbuttons = 0;

- if(m & NSAlternateKeyMask)

+ if(m & NSControlKeyMask)

+ in.kbuttons |= 1;

+ if(m & NSAlternateKeyMask)

in.kbuttons |= 2;

if(m & NSCommandKeyMask)

in.kbuttons |= 4;

And now you can press Ctrl while having Alt pressed to send a "button 1" chord. Simple and innocuous patch.